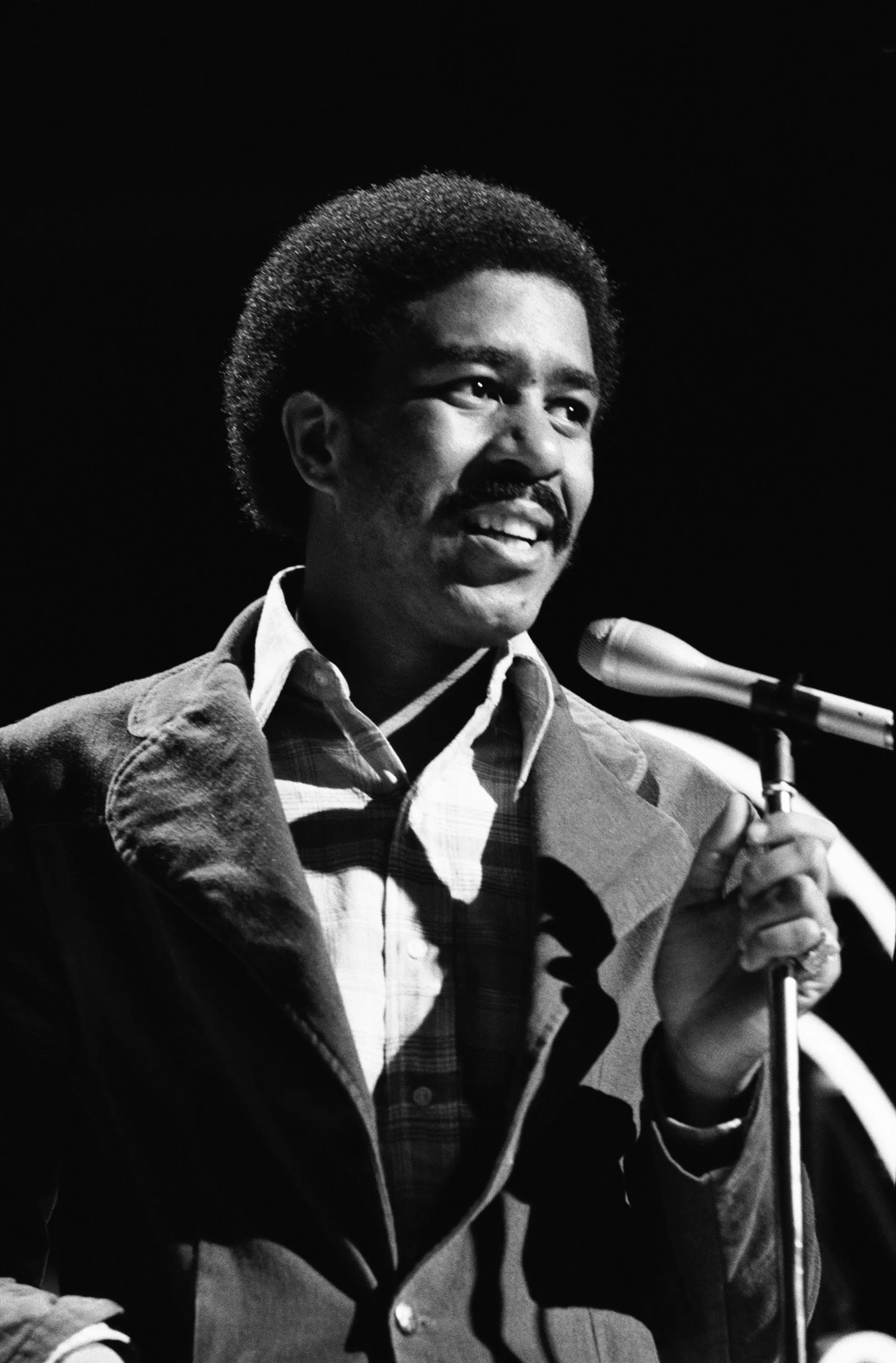

Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor Sr. (December 1, 1940 – December 10, 2005) was an American stand-up comedian and actor. He reached a broad audience with his trenchant observations and storytelling style and is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most important stand-up comedians of all time. Pryor won a Primetime Emmy Award and five Grammy Awards. He received the first Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in 1998. He won the Writers Guild of America Award in 1974. He was listed at number one on Comedy Central’s list of all-time greatest stand-up comedians. In 2017, Rolling Stone ranked him first on its list of the 50 best stand-up comics of all time.

Pryor’s body of work includes the concert films and recordings: Richard Pryor: Live & Smokin’ (1971), That Nigger’s Crazy (1974), …Is It Something I Said? (1975), Bicentennial Nigger (1976), Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1979), Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (1982), and Richard Pryor: Here and Now (1983). As an actor, he starred mainly in comedies. His occasional roles in dramas included Paul Schrader’s Blue Collar (1978). He also appeared in action films, like Superman III (1983). He collaborated on many projects with actor Gene Wilder, including the films Silver Streak (1976), Stir Crazy (1980), See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989), and Another You (1991).

Pryor was born on December 1, 1940, in Peoria, Illinois. He grew up in a brothel run by his grandmother, Marie Carter, where his alcoholic mother, Gertrude L. (née Thomas), was a prostitute. His father, LeRoy “Buck Carter” Pryor (June 7, 1915 – September 27, 1968), was a former boxer, hustler and pimp. After Gertrude abandoned him when he was 10, Pryor was raised primarily by Marie, a tall, violent woman who would beat him for any of his eccentricities. Pryor was one of four children raised in his grandmother’s brothel. He was sexually abused at age seven and expelled from school at the age of 14. While in Peoria, he became a Prince Hall Freemason at a local lodge.

Pryor served in the U.S. Army from 1958 to 1960 but spent virtually the entire stint in an army prison. According to a 1999 profile about Pryor in The New Yorker, Pryor was incarcerated for an incident that occurred while he was stationed in West Germany. Angered that a white soldier was overly amused at the racially charged scenes of Douglas Sirk’s film Imitation of Life, Pryor and several other black soldiers beat and stabbed him, although not fatally.

In 1963, Pryor moved to New York City and began performing regularly in clubs alongside performers such as Bob Dylan and Woody Allen. On one of his first nights, he opened for singer and pianist Nina Simone at New York’s Village Gate. Simone recalls Pryor’s bout of performance anxiety:

He shook like he had malaria; he was so nervous. I couldn’t bear to watch him shiver, so I put my arms around him there in the dark and rocked him like a baby until he calmed down. The next night was the same, and the next, and I rocked him each time.[10]

Inspired by Bill Cosby, Pryor began as a middlebrow comic, with material less controversial than what was to come. He began appearing regularly on television variety shows such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Merv Griffin Show, and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. His popularity led to success as a comic in Las Vegas. The first five tracks on the 2005 compilation CD Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966–1974), recorded in 1966 and 1967, capture Pryor in this period. In 1966, Pryor was a guest star on an episode of The Wild Wild West.

In September 1967, Pryor had what he described in his autobiography Pryor Convictions (1995) as an “epiphany”. He walked onto the stage at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas (with Dean Martin in the audience), looked at the sold-out crowd, exclaimed over the microphone, “What the fuck am I doing here!?”, and walked off the stage. Afterward, Pryor began working profanity into his act, including the word nigger. His first comedy recording, the 1968 debut Richard Pryor on the Dove/Reprise label, captures this particular period, tracking the evolution of Pryor’s routine. Around this time, his parents died—his mother in 1967 and his father in 1968.

In 1969, Pryor moved to Berkeley, California, where he immersed himself in the counterculture and met people like Huey P. Newton and Ishmael Reed.

In the 1970s, Pryor wrote for television shows such as Sanford and Son, The Flip Wilson Show, and a 1973 Lily Tomlin special, for which he shared an Emmy Award. During this period, Pryor tried to break into mainstream television. He appeared in several films, including Lady Sings the Blues (1972), The Mack (1973), Uptown Saturday Night (1974), Silver Streak (1976), Car Wash (1976), Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings (1976), Which Way Is Up? (1977), Greased Lightning (1977), Blue Collar (1978), and The Muppet Movie (1979).

Pryor signed with the comedy-oriented independent record label Laff Records in 1970, and in 1971 recorded his second album, Craps (After Hours). Two years later Pryor, still relatively unknown, appeared in the documentary Wattstax (1972), wherein he riffed on the tragic-comic absurdities of race relations in Watts and the United States. Not long afterward, Pryor sought a deal with a larger label, and he signed with Stax Records in 1973. When his third, breakthrough album, That Nigger’s Crazy (1974), was released, Laff, which claimed ownership of Pryor’s recording rights, almost succeeded in getting an injunction to prevent the album from being sold. Negotiations led to Pryor’s release from his Laff contract. In return for this concession, Laff was enabled to release previously unissued material, recorded between 1968 and 1973, at will. That Nigger’s Crazy was a commercial and critical success; it was eventually certified gold by the RIAA and won the Grammy Award for Best Comedy Album at the 1975 Grammy Awards.

During the legal battle, Stax briefly closed its doors. At this time, Pryor returned to Reprise/Warner Bros. Records, which re-released That Nigger’s Crazy, immediately after…Is It Something I Said? his first album with his new label. Like That Nigger’s Crazy, the album was a critical success; it was eventually certified platinum by the RIAA and won the Grammy Award for Best Comedy Recording at the 1976 Grammy Awards.

Pryor’s 1976 release Bicentennial Nigger continued his streak of success. It became his third consecutive gold album, and he collected his third consecutive Grammy for Best Comedy Recording for the album in 1977. With every successful album Pryor recorded for Warner (or later, his concert films and his 1980 freebasing accident), Laff published an album of older material to capitalize on Pryor’s growing fame—a practice they continued until 1983. The covers of Laff albums tied in thematically with Pryor films, such as Are You Serious? for Silver Streak (1976), The Wizard of Comedy for his appearance in The Wiz (1978), and Insane for Stir Crazy (1980).

Pryor co-wrote Blazing Saddles (1974), directed by Mel Brooks and starring Gene Wilder. Pryor was to play the lead role of Bart, but the film’s production studio would not insure him, and Mel Brooks chose Cleavon Little instead.

In 1975, Pryor was a guest host on the first season of Saturday Night Live (SNL) and the first black person to host the show. Pryor’s longtime girlfriend, actress and talk-show host Kathrine McKee (sister of Lonette McKee) made a brief guest appearance with Pryor on SNL. One of the highlights of the night was the controversial “word association” skit with Chevy Chase. He would later do his own variety show, The Richard Pryor Show, which premiered on NBC in 1977. The show was cancelled after only four episodes probably because television audiences did not respond well to his show’s controversial subject matter, and Pryor was unwilling to alter his material for network censors. He later said, “They offered me ten episodes, but I said all I wanted to in four.” During the short-lived series, he portrayed the first black President of the United States, spoofed the Star Wars Mos Eisley cantina, examined gun violence in a non-comedy skit, lampooned racism on the sinking Titanic and used costumes and visual distortion to appear nude.

In 1979, at the height of his success, Pryor visited Kenya. Upon returning to the United States from Africa, Pryor swore he would never use the word “nigger” in his stand-up comedy routine again.

In 1980, Pryor became the first black actor to earn a million dollars for a single film when he was hired to star in Stir Crazy. On June 9, 1980, while on a freebasing binge during the making of the film, Pryor doused himself in rum and set himself on fire. Pryor incorporated a description of the incident into his comedy show Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (1982). He joked that the event was caused by dunking a cookie into a glass of low-fat and pasteurized milk, causing an explosion. At the end of the bit, he poked fun at people who told jokes about it by waving a lit match and saying, “What’s that? Richard Pryor running down the street.”

Before the freebasing incident, Pryor was about to start filming Mel Brooks’ History of the World, Part I (1981), but was replaced at the last minute by Gregory Hines. Likewise, Pryor was scheduled for an appearance on The Muppet Show at that time, which forced the producers to cast their British writer, Chris Langham, as the guest star for that episode instead.

After his “final performance”, Pryor did not stay away from stand-up comedy for long. Within a year, he filmed and released a new concert film and accompanying album, Richard Pryor: Here and Now (1983), which he directed himself. He wrote and directed a fictionalized account of his life, Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling, which was inspired by the 1980 freebasing incident.

In 1983 Pryor signed a five-year contract with Columbia Pictures for $40 million and he started his own production company, Indigo Productions. Softer, more formulaic films followed, including Superman III (1983), which earned Pryor $4 million; Brewster’s Millions (1985), Moving (1988), and See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989). The only film project from this period that recalled his rough roots was Pryor’s semiauto biographic debut as a writer-director, Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling, which was not a major success.

Pryor was also originally considered for the role of Billy Ray Valentine on Trading Places (1983), before Eddie Murphy won the part.

Despite his reputation for constantly using profanity on and off camera, Pryor briefly hosted a children’s show on CBS called Pryor’s Place (1984). Like Sesame Street (where Pryor appeared in a few oft-repeated segments), Pryor’s Place featured a cast of puppets (animated by Sid and Marty Krofft), hanging out and having fun in a friendly inner-city environment along with several children and characters portrayed by Pryor himself. Its theme song was performed by Ray Parker Jr. Pryor’s Place frequently dealt with more sobering issues than Sesame Street. It was cancelled shortly after its debut.

Pryor co-hosted the Academy Awards twice and was nominated for an Emmy for a guest role on the television series Chicago Hope. Network censors had warned Pryor about his profanity for the Academy Awards, and after a slip early in the program, a five-second delay was instituted when returning from a commercial break. Pryor is one of only three Saturday Night Live hosts to be subjected to a rare five-second delay for his 1975 appearance (along with Sam Kinison in 1986 and Andrew Dice Clay in 1990).

Pryor developed a reputation for being demanding and disrespectful on film sets, and for making selfish and difficult requests. In his autobiography Kiss Me Like a Stranger, co-star Gene Wilder says that Pryor was frequently late to the set during filming of Stir Crazy, and that he demanded, among other things, a helicopter to fly him to and from set because he was the star. Pryor was accused of using allegations of on-set racism to force the hand of film producers into giving him more money.

Pryor appeared in Harlem Nights (1989), a comedy-drama crime film starring three generations of black comedians (Pryor, Eddie Murphy, and Redd Foxx).

In November 1977, after many years of heavy smoking and drinking, Pryor had a mild heart attack at age 36. He recovered and resumed performing in January the following year. In 1986, he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. In 1990, Pryor had a second heart attack while in Australia. He underwent triple heart bypass surgery in 1991.

In late 2004, his sister said he had lost his voice as a result of his multiple sclerosis. However, on January 9, 2005, Pryor’s wife, Jennifer Lee, rebutted this statement in a post on Pryor’s official website, citing Richard as saying: “I’m sick of hearing this shit about me not talking … not true … I have good days, bad days … but I still am a talkin’ motherfucker!”

On the morning of December 10, 2005, Pryor had a third heart attack at his house in Los Angeles. After his wife’s failed attempts to resuscitate him, he was taken to a local Westside hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 7:58 a.m. PST at age 65. His widow Jennifer was quoted as saying, “At the end, there was a smile on his face.”

He was cremated, and his ashes were given to his family. His ashes were scattered in the bay at Hana, Hawaii, by his widow in 2019. Forensic pathologist Michael Hunter believes Pryor’s fatal heart attack was caused by coronary artery disease that was at least partially brought about by years of tobacco smoking.

Written by Dianne Washington