Mildred “Candi” Thorpe, tap dancer who was a member of the famed duet duo Candi and Pepper, was one of four children (two boys and two girls) born to William Thomas Thorpe, of African American and Native American heritage who migrated to Philadelphia in 1905 in the midst of the Great Migration; and Laura Decker Thorpe, of Pennsylvanian Dutch and African-American heritage. Young Thorpe attended Saint Peter Claver’s Parochial school and Auden Reed Junior High School, dropping out of school when she was in the ninth grade to pursue her dance career. Though she never went to dancing school, she saw performances at the Lincoln Theatre, a black vaudeville theater in Philadelphia, where she learned tap dance steps from such legendary hoofers as Bill Bailey, Derby Wilson, and Charles “Honi” Coles. After learning a step from Coles, he remarked, “I liked the way you did it better.” Around 1935 when she was sixteen, she joined a traveling troupe of eight tap dancers who performed in a carnival and billed as “Tally’s Minstrels”; the troupe performed songs and dances in blackface in a one-hour show held in a tent and part of the larger carnival tent show. In Hopkinsville, Kentucky, the owners deserted the carnival and ran off with the money, leaving Thorpe to return to Philadelphia to work as a solo performer in local nightclubs.

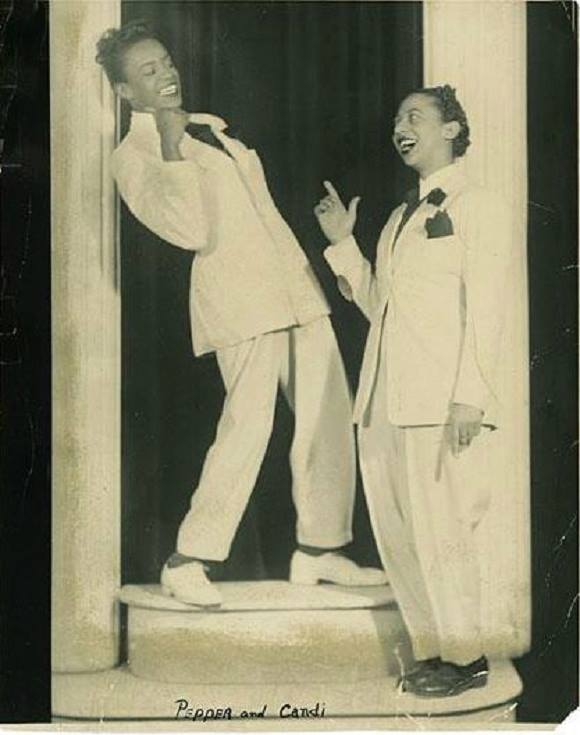

In 1939, while working at the Congo Club, Thorpe met her first dance partner, Jewel “Pepper” Welch; they performed their first engagement at Simm’s Paradise in Philadelphia as the tap dance team “Candi and Pepper.” In short time, their manager, Reiss DuPree, booked them at New York’s Apollo Theater, home to thousands of African-American performers. The Apollo was known for its fierce competitive spirit; an audience had the power to make or break careers. “Candi and Pepper” made their debut at the Apollo in 1941 as the opening act, on the same bill as Fats Waller and his band and comedy singers “Apus and Estrellita.” The master of ceremonies announced them: “Ladies and Gentlemen, we got two girls who are going to dance for you out of Philadelphia. Candi is sweet, Pepper is hot; come on girls show me what you’ve got.” As Thorpe remembered “We tore ‘em up. We tore ‘em up!” They were called back onstage for so many encores they ran out of routines. After their first performance they replaced “Stump and Stumpy” (who regularly closed the show) as the closing act, thereby gaining the highest billing. The Apollo success helped launch the team into an active performing career as they toured the East coast and Mid-West as featured performers with such musical stars as Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller and Erkstine Hawkins.

Candi and Pepper began their act with a jazz song, such as “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” to which they added some dance movement. Then Thorpe performed her rhythm tap dance solo to “I’ve Got Rhythm,” played in stop-time, allowing her to perform her rhythmic breaks without musical accompaniment. An improvisational dancer in the tradition of Baby Laurence, Teddy Hale, and Eddie Brown, she was comfortable expressing herself rhythmically, adding slides, wings, and trenches while dancing. “I’m an innovator,” she explained. “What I think is no particular sound or music that goes with it. I could just go out there and dance without music. It swings. It’s just a mover and a shaker.” “Pepper” Welch followed Thorpe with her expressive style of flash dancing. Tall, and with a beautiful style of moving, Welch added quick turns to her dancing, her jacket flowing around her body. “I played to the audience,” Welch recalled. “I looked to make each person think I was dancing for them.” They closed their act to “One O’Clock Jump,” performing trench steps and straddle splits jumps, in which they touched their toes, and their version of Russian-styled kazotsky kicks.

Thorpe was often complimented by predominantly male African-American tap dancers as being “that girl who could dance her ass off”: in the 1930s and 40s, that was considered the highest compliment a female dancer could receive, as it meant that this dancer’s skills incorporated swinging rhythmic phrases, some elements of surprise (flash, acrobatics, eccentric), and personal style. When the Candi and Pepper team broke apart in the early 1940s, 1944 to be exact. Thorpe remained in Chicago for a few years and thereafter retired from show business.

Written by Dianne Washington