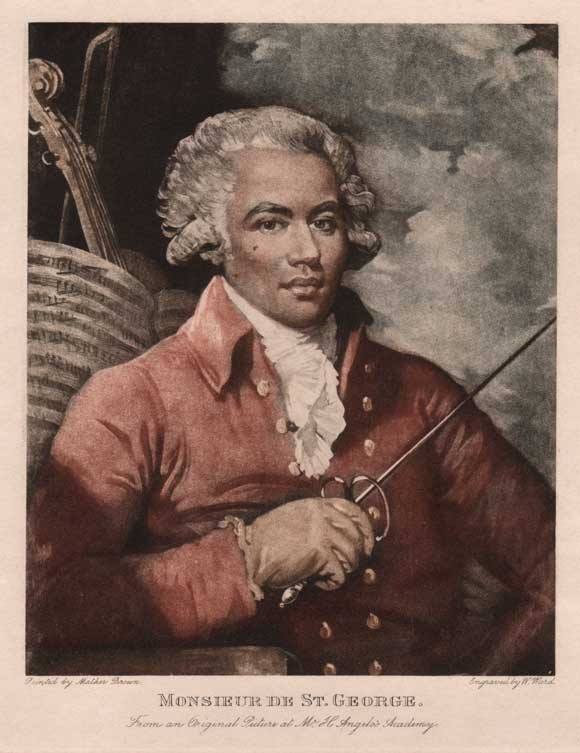

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (December 25, 1745 – June 10, 1799) was a champion fencer, virtuoso violinist, and conductor of the leading symphony orchestra in Paris. Born in Guadeloupe, he was the son of George Bologne de Saint-Georges, a wealthy planter, and Nanon, his African slave. During the French Revolution, Saint-Georges was colonel of the Légion St.-Georges, the first all-black regiment in Europe, fighting on the side of the Republic. Today the Chevalier de Saint-Georges is best remembered as the first classical composer of African ancestry.

Boulogne was born on the West Indies island of Guadeloupe, where his mother Nanon was a slave. Boulogne’s father was a Frenchman, George de Bologne Saint-Georges. He owned the plantation on which Joseph spent his early childhood. The word “Chevalier” means “Knight” in French. It was a title of nobility in the Kingdom of France. Joseph could not inherit his father’s status as a member of the nobility because his mother was an African.

Even so, he was called “Chevalier de Saint-Georges” from a young age. At age 10, Saint-Georges moved to France with his parents. There he continued his studies in classical music. He was tutored in violin by Jean-Marie Leclair, and studied composition with Francois-Joseph Gossec. Saint-Georges also spent six years at the boarding school of Texier de La Boessiere, a master of arms. Athletics and fencing brought him a reputation at an early age. He swam across the River Seine in winter with one arm tied behind his back. As an adult he signed his surname “Saint-George” and that became the normal spelling in French. Saint-George’s’ military career began in 1761 as an officer in the King’s Guard.

In his music career, the conductor of the prestigious Le Concert des Amateurs orchestra chose Saint-Georges as First Violin in 1769. Saint-Georges made his public debut as a violin soloist during the 1772-73 concert season, performing his own violin concertos. Many say that Saint-Georges demonstrated the influence of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. He has even been called “Le Mozart Noir” or “The Black Mozart.” History shows that Mozart came to Paris in 1778 to study the ”Paris School” of composition while Saint-Georges was a member.

In 1775, Queen Marie-Antoniette appointed Saint-Georges as her music director, and King Louis XVI named him director of the Paris Opera. Saint-Georges was also the first person of African descent to join a Masonic Lodge in France. He was initiated in Paris to “Les 9 Soeurs,” a Lodge belonging to the Grand Orient of France.

As a conductor, he later traveled to Vienna and commissioned Franz Joseph Haydn to compose the Paris Symphonies, Nos. 82-87, which premiered in 1787. No. 85, called The Queen, was a favorite of Marie-Antoniette.

Saint-Georges joined the pro-Revolution National Guard in 1789. That same year the Declaration of the Rights of Man was issued by the National Assembly. On Sept. 7, 1792, a delegation of men of color asked the National Assembly to allow them to fight in defense of the Revolution and its egalitarian ideals. On the next day the Assembly, authorized the Légion des Hussards Américains [Legion of American Soldiers], which had 1,000 volunteers of color, with Saint-Georges as their colonel. One of its squadron leaders was Alexandre Dumas Davy de La Pailleterie (1762-1806). Like his colonel, he was the son of a French aristocrat and an African slave. He later had a son, Alexander Dumas, who wrote “The Three Musketeers.”

On September 25, 1793, Saint-Georges lost his command due to false charges of misusing public funds. He spent 18 months in the house of detention at Houdainville before being acquitted. After his release Saint-Georges took part in the Haitian Revolution.

Saint-Georges produced 14 violin concertos and 9 symphonies between 1773 and 1785. He wrote 2 solo violins, 2 symphonies, 3 sonatas for violin and harpsichord, and 18 string quartets divided into 3 collections of 6 quartets in each. Saint-Georges also composed several operas for the Comedie-Italienne, beginning in 1777.

Saint-Georges lived alone in a small apartment in Paris during the final two years of his life. He died of gangrene in a leg wound on June 12, 1799.

Written by Dianne Washington