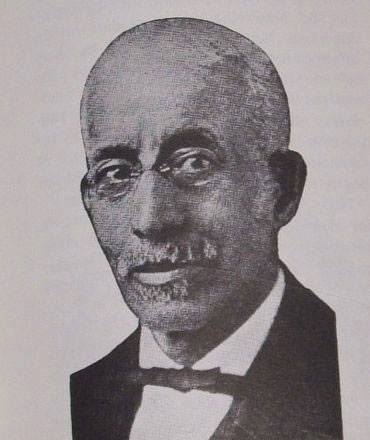

John Henry Murphy, Sr. was an African-American newspaper publisher, best known as founder of the Baltimore Afro-American (also known as The Afro), published by the Afro-American Newspaper Company of Baltimore, Inc. This newspaper is one of the oldest remaining family-owned newspapers in the U.S.

According to the 1860 United States Federal Census, Murphy was born in Baltimore, Maryland, to Benjamin and Susan Murphy (nee Colby). He is popularly believed to have been enslaved until mustering into United States Colored Infantry’s 30th Regiment in Camp Stanton, Maryland in February 1864. He served as a non-commissioned officer.

In 1868 he married Martha Elizabeth Howard, a daughter of the well-to-do African-American landowner, Enoch George Howard of Montgomery County, Maryland. Murphy and his wife had 11 children in all, 10 of whom survived to adulthood. After his death, several of his descendants led the paper over the course of several generations, including his grandson, John H. Murphy, III.

Using proceeds from a land sale by his wife, Murphy was able to acquire from Rev. Harry Bragg, Sr. the publication, The Afro-American, in 1892 and merge it with his pre-existing publications, The Sunday School Helper and The Ledger.

Little is known about Murphy before his service in the American Civil War, among the over 8,000 United States Colored Troops who mustered into regiments throughout the State of Maryland.

After the war, Murphy returned home and worked as a whitewasher, a trade he learned from his father. The development of wallpaper at prices available to the middle class made whitewashing obsolete. Murphy was appointed to the federal civil service in the postal service. He later worked in various jobs: as a porter, janitor, manager of a feed store, and manager of the printing department of the Afro-American,published by Rev. Harry Bragg Sr. for his church.

During these years, Murphy became active with Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, founded in Philadelphia in the early 19th century as the first black denomination in the United States. After being appointed as a District Sunday School Superintendent, Murphy used a manual printing press to produce a weekly church publication, the Sunday School Helper, to make copies of materials for students. In 1897 Murphy purchased the printing presses of the Afro-American at auction with $200 borrowed from his wife, who had sold land inherited from her father. He merged the Sunday School Helper with the Afro. In 1900, he acquired another newspaper, The Ledger, and renamed his paper as The Afro-American Ledger.

Murphy helped build the African-American community in Baltimore by sharing its news, pressing for civil rights, and reporting on abuses. At first his family worked unpaid for the paper. Later he had up to 100 employees. “He crusaded for racial justice while exposing racism in education, jobs, housing, and public accommodations. In 1913, he was elected president of the National Negro Press Association.”

Due to the economic and political power of blacks in Baltimore, who comprised a large community, and the activism of people like Murphy, the Maryland state legislature did not follow the example of other southern states and disenfranchise black voters at the turn of the century. African Americans struggled with discrimination in the city but maintained more freedom and political power than blacks in most other southern states.

His son Carl Murphy, by then having a doctorate from the University of Jena in Germany and serving as head of the German department at Howard University, returned to Baltimore in 1918 to work on the paper in his father’s last years. In 1922, after his father’s death, Carl J. Murphy was named as editor and publisher of the paper.

After John Henry Murphy’s death on April 5, 1922, his descendants led the newspaper over the course of the next generations, including son Carl J. Murphy for 45 years, and John’s grandson and namesake, John H. Murphy, III.

Written by Dianne Washington