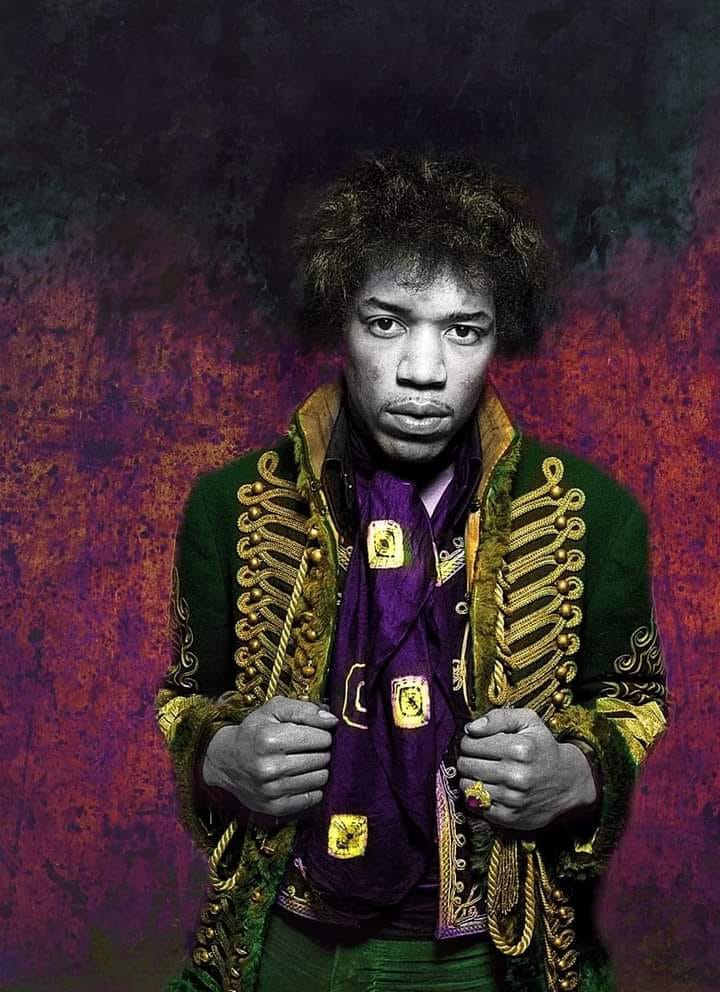

James Marshall “Jimi” Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942 – September 18, 1970) was an American rock guitarist, singer, and songwriter. Although his mainstream career spanned only four years, he is widely regarded as one of the most influential electric guitarists in the history of popular music, and one of the most celebrated musicians of the 20th century. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame describes him as “arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music”.

Born in Seattle, Washington, Hendrix began playing guitar at the age of 15. In 1961, he enlisted in the US Army and trained as a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne Division; he was granted an honorable discharge the following year. Soon afterward, he moved to Clarksville, Tennessee, and began playing gigs on the Chitlin’ Circuit, earning a place in the Isley Brothers’ backing band and later with Little Richard, with whom he continued to work through mid-1965. He then played with Curtis Knight and the Squires before moving to England in late 1966 after being discovered by Linda Keith, who in turn interested bassist Chas Chandler of the Animals in becoming his first manager. Within months, Hendrix had earned three UK top ten hits with the Jimi Hendrix Experience: “Hey Joe”, “Purple Haze”, and “The Wind Cries Mary”. He achieved fame in the US after his performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and in 1968 his third and final studio album, Electric Ladyland, reached number one in the US; it was Hendrix’s most commercially successful release and his first and only number one album. The world’s highest-paid performer, he headlined the Woodstock Festival in 1969 and the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970 before his accidental death from barbiturate-related asphyxia on September 18, 1970, at the age of 27.

Hendrix was inspired musically by American rock and roll and electric blues. He favored overdriven amplifiers with high volume and gain, and was instrumental in utilizing the previously undesirable sounds caused by guitar amplifier feedback. He helped to popularize the use of a wah-wah pedal in mainstream rock, and was the first artist to use stereophonic phasing effects in music recordings. Holly George-Warren of Rolling Stone commented: “Hendrix pioneered the use of the instrument as an electronic sound source. Players before him had experimented with feedback and distortion, but Hendrix turned those effects and others into a controlled, fluid vocabulary every bit as personal as the blues with which he began.”

Hendrix was the recipient of several music awards during his lifetime and posthumously. In 1967, readers of Melody Maker voted him the Pop Musician of the Year, and in 1968, Rolling Stone declared him the Performer of the Year. Disc and Music Echo honored him with the World Top Musician of 1969 and in 1970, Guitar Player named him the Rock Guitarist of the Year. The Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005. Rolling Stone ranked the band’s three studio albums, Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love, and Electric Ladyland, among the 100 greatest albums of all time, and they ranked Hendrix as the greatest guitarist and the sixth greatest artist of all time.

Jimi Hendrix was of African-American descent. Both his mother Lucille and father Al were African-Americans. His paternal grandmother, Zenora “Nora” Rose Moore, was African-American and one-quarter Cherokee. Hendrix’s paternal grandfather, Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix (born 1866), was the result of an extramarital affair between a woman named Fanny, and a grain merchant from Urbana, Ohio or Illinois, one of the wealthiest men in the area at that time. On June 10, 1919, Hendrix and Moore had a son they named James Allen Ross Hendrix; people called him Al

In 1941, Al met Lucille Jeter (1925–1958) at a dance in Seattle; they married on March 31, 1942. Al, who had been drafted by the U.S. Army to serve in World War II, left to begin his basic training three days after the wedding. Johnny Allen Hendrix was born on November 27, 1942, in Seattle, Washington; he was the first of Lucille’s five children. In 1946, Johnny’s parents changed his name to James Marshall Hendrix, in honor of Al and his late brother Leon Marshall.

Stationed in Alabama at the time of Hendrix’s birth, Al was denied the standard military furlough afforded servicemen for childbirth; his commanding officer placed him in the stockade to prevent him from going AWOL to see his infant son in Seattle. He spent two months locked up without trial, and while in the stockade received a telegram announcing his son’s birth. During Al’s three-year absence, Lucille struggled to raise their son. When Al was away, Hendrix was mostly cared for by family members and friends, especially Lucille’s sister Delores Hall and her friend Dorothy Harding. Al received an honorable discharge from the US Army on September 1, 1945. Two months later, unable to find Lucille, Al went to the Berkeley, California home of a family friend named Mrs. Champ, who had taken care of and had attempted to adopt Hendrix; this is where Al saw his son for the first time.

After returning from service, Al reunited with Lucille, but his inability to find steady work left the family impoverished. They both struggled with alcohol, and often fought when intoxicated. The violence sometimes drove Hendrix to withdraw and hide in a closet in their home. His relationship with his brother Leon (born 1948) was close but precarious; with Leon in and out of foster care, they lived with an almost constant threat of fraternal separation. In addition to Leon, Hendrix had three younger siblings: Joseph, born in 1949, Kathy in 1950, and Pamela, 1951, all of whom Al and Lucille gave up to foster care and adoption. The family frequently moved, staying in cheap hotels and apartments around Seattle. On occasion, family members would take Hendrix to Vancouver to stay at his grandmother’s. A shy and sensitive boy, he was deeply affected by his life experiences. In later years, he confided to a girlfriend that he had been the victim of sexual abuse by a man in uniform. On December 17, 1951, when Hendrix was nine years old, his parents divorced; the court granted Al custody of him and Leon.

In September 1963, after Cox was discharged from the Army, he and Hendrix moved to Clarksville, Tennessee, and formed a band called the King Kasuals. Hendrix had watched Butch Snipes play with his teeth in Seattle and by now Alphonso ‘Baby Boo’ Young, the other guitarist in the band, was performing this guitar gimmick. Not to be upstaged, Hendrix learned to play with his teeth. He later commented: “The idea of doing that came to me…in Tennessee. Down there you have to play with your teeth or else you get shot. There’s a trail of broken teeth all over the stage.” Although they began playing low-paying gigs at obscure venues, the band eventually moved to Nashville’s Jefferson Street, which was the traditional heart of the city’s black community and home to a thriving rhythm and blues music scene. They earned a brief residency playing at a popular venue in town, the Club del Morocco, and for the next two years Hendrix made a living performing at a circuit of venues throughout the South that were affiliated with the Theater Owners’ Booking Association (TOBA), widely known as the Chitlin’ Circuit. In addition to playing in his own band, Hendrix performed as a backing musician for various soul, R&B, and blues musicians, including Wilson Pickett, Slim Harpo, Sam Cooke, and Jackie Wilson.

In January 1964, feeling he had outgrown the circuit artistically, and frustrated by having to follow the rules of bandleaders, Hendrix decided to venture out on his own. He moved into the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, where he befriended Lithofayne Pridgon, known as “Faye”, who became his girlfriend. A Harlem native with connections throughout the area’s music scene, Pridgon provided him with shelter, support, and encouragement. Hendrix also met the Allen twins, Arthur and Albert. In February 1964, Hendrix won first prize in the Apollo Theater amateur contest. Hoping to secure a career opportunity, he played the Harlem club circuit and sat in with various bands. At the recommendation of a former associate of Joe Tex, Ronnie Isley granted Hendrix an audition that led to an offer to become the guitarist with the Isley Brothers’ back-up band, the I.B. Specials, which he readily accepted.

In March 1964, Hendrix recorded the two-part single “Testify” with the Isley Brothers. Released in June, it failed to chart. In May, he provided guitar instrumentation for the Don Covay song, “Mercy Mercy”. Issued in August by Rosemart Records and distributed by Atlantic, the track reached number 35 on the Billboard chart.

Hendrix toured with the Isleys during much of 1964, but near the end of October, after growing tired of playing the same set every night, he left the band. Soon afterward, Hendrix joined Little Richard’s touring band, the Upsetters. During a stop in Los Angeles in February 1965, he recorded his first and only single with Richard, “I Don’t Know What You Got (But It’s Got Me)”, written by Don Covay and released by Vee-Jay Records. Richard’s popularity was waning at the time, and the single peaked at number 92, where it remained for one week before dropping off the chart. Hendrix met singer Rosa Lee Brooks while staying at the Wilcox Hotel in Hollywood, and she invited him to participate in a recording session for her single, which included the Arthur Lee penned “My Diary” as the A-side, and “Utee” as the B-side. Hendrix played guitar on both tracks, which also included background vocals by Lee. The single failed to chart, but Hendrix and Lee began a friendship that lasted several years; Hendrix later became an ardent supporter of Lee’s band, Love.

In July 1965, on Nashville’s Channel 5 Night Train, Hendrix made his first television appearance. Performing in Little Richard’s ensemble band, he backed up vocalists Buddy and Stacy on “Shotgun”. The video recording of the show marks the earliest known footage of Hendrix performing. Richard and Hendrix often clashed over tardiness, wardrobe, and Hendrix’s stage antics, and in late July, Richard’s brother Robert fired him. He then briefly rejoined the Isley Brothers, and recorded a second single with them, “Move Over and Let Me Dance” backed with “Have You Ever Been Disappointed”. Later that year, he joined a New York-based R&B band, Curtis Knight and the Squires, after meeting Knight in the lobby of a hotel where both men were staying. Hendrix performed with them for eight months. In October 1965, he and Knight recorded the single, “How Would You Feel” backed with “Welcome Home” and on October 15, Hendrix signed a three-year recording contract with entrepreneur Ed Chalpin. While the relationship with Chalpin was short-lived, his contract remained in force, which later caused legal and career problems for Hendrix. During his time with Knight, Hendrix briefly toured with Joey Dee and the Starliters, and worked with King Curtis on several recordings including Ray Sharpe’s two-part single, “Help Me” Hendrix earned his first composer credits for two instrumentals, “Hornets Nest” and “Knock Yourself Out”, released as a Curtis Knight and the Squires single in 1966.

Feeling restricted by his experiences as an R&B sideman, Hendrix moved to New York City’s Greenwich Village in 1966, which had a vibrant and diverse music scene. There, he was offered a residency at the Cafe Wha? on MacDougal Street and formed his own band that June, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, which included future Spirit guitarist Randy California. The Blue Flames played at several clubs in New York and Hendrix began developing his guitar style and material that he would soon use with the Experience. In September, they gave some of their last concerts at the Cafe au Go Go, as John Hammond Jr.’s backing group

In 1966, while leading his own band in Greenwich Village in New York City, where he had attracted a small following, Hendrix was noticed by British rock musician Chas Chandler, who took him to London and introduced him to Noel Redding, a bass player, and Mitch Mitchell, a drummer.

As a trio, they formed the group called The Jimi Hendrix Experience. With this group Hendrix rapidly became popular in Europe, and his reputation preceded his return to the United States. His appearance at the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967 was a watershed of his career, as was the success of his album “Are You Experienced?” that same year. These two events lifted him to instant rock stardom. Another album, “Electric Ladyland”(1968), was one of the most influential rock records of the 1960s.

Hendrix was an outstanding blues guitarist working in a rock idiom. The melodic lines of his extended solos were alternately ragged, soaring, or rhythmically driving, while his phrasing was augmented by the use of extremely high volume and electronic distortion. His playing had a sensuous, exotic quality that was original and instantly recognizable.

In January 1969, after an absence of more than six months, Hendrix briefly moved back into his girlfriend Kathy Etchingham’s Brook Street apartment, which was next door to the Handel House Museum in the West End of London. During this time, the Experience toured Scandinavia, Germany, and gave their final two performances in France. On February 18 and 24, they played sold-out concerts at London’s Royal Albert Hall, which were the last European appearances of this line-up.

By February 1969, Redding had grown weary of Hendrix’s unpredictable work ethic and his creative control over the Experience’s music. During the previous month’s European tour, interpersonal relations within the group had deteriorated, particularly between Hendrix and Redding. In his diary, Redding documented the building frustration during early 1969 recording sessions: “On the first day, as I nearly expected, there was nothing doing … On the second it was no show at all. I went to the pub for three hours, came back, and it was still ages before Jimi ambled in. Then we argued … On the last day, I just watched it happen for a while, and then went back to my flat.” The last Experience sessions that included Redding—a re-recording of “Stone Free” for use as a possible single release—took place on April 14 at Olmstead and the Record Plant in New York Hendrix then flew bassist Billy Cox to New York; they started recording and rehearsing together on April 21.

The last performance of the original Experience line-up took place on June 29, 1969, at Barry Fey’s Denver Pop Festival, a three-day event held at Denver’s Mile High Stadium that was marked by police using tear gas to control the audience. The band narrowly escaped from the venue in the back of a rental truck, which was partly crushed by fans who had climbed on top of the vehicle. Before the show, a journalist angered Redding by asking why he was there; the reporter then informed him that two weeks earlier Hendrix announced that he had been replaced with Billy Cox. The next day, Redding quit the Experience and returned to London. He announced that he had left the band and intended to pursue a solo career, blaming Hendrix’s plans to expand the group without allowing for his input as a primary reason for leaving. Redding later commented: “Mitch and I hung out a lot together, but we’re English. If we’d go out, Jimi would stay in his room. But any bad feelings came from us being three guys who were traveling too hard, getting too tired, and taking too many drugs … I liked Hendrix. I don’t like Mitchell.”

Soon after Redding’s departure, Hendrix began lodging at the eight-bedroom Ashokan House, in the hamlet of Boiceville near Woodstock in upstate New York, where he had spent some time vacationing in mid-1969. Manager Michael Jeffery arranged the accommodations in the hope that the respite might encourage Hendrix to write material for a new album. During this time, Mitchell was unavailable for commitments made by Jeffery, which included Hendrix’s first appearance on U.S. TV—on The Dick Cavett Show—where he was backed by the studio orchestra, and an appearance on The Tonight Show where he appeared with Cox and session drummer Ed Shaughnessy.

By 1969, Hendrix was the world’s highest-paid rock musician. In August, he headlined the Woodstock Music and Art Fair that included many of the most popular bands of the time. For the concert, he added rhythm guitarist Larry Lee and conga players Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez. The band rehearsed for less than two weeks before the performance, and according to Mitchell, they never connected musically. Before arriving at the engagement, he heard reports that the size of the audience had grown to epic proportions, which gave him cause for concern as he did not enjoy performing for large crowds. He was an important draw for the event, and although he accepted substantially less money for the appearance than his usual fee, he was the festival’s highest-paid performer. As his scheduled time slot of midnight on Sunday drew closer, he indicated that he preferred to wait and close the show in the morning; the band took the stage around 8:00 a.m. on Monday. By the time of their set, Hendrix had been awake for more than three days. The audience, which peaked at an estimated 400,000 people, was now reduced to 30–40,000, many of whom had waited to catch a glimpse of Hendrix before leaving during his performance. The festival MC, Chip Monck, introduced the group as the Jimi Hendrix Experience, but Hendrix clarified: “We decided to change the whole thing around and call it Gypsy Sun and Rainbows. For short, it’s nothin’ but a Band of Gypsys”.

Hendrix’s performance featured a rendition of the U.S. national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner”, during which he used copious amounts of amplifier feedback, distortion, and sustain to replicate the sounds made by rockets and bombs. Although contemporary political pundits described his interpretation as a statement against the Vietnam War, three weeks later Hendrix explained its meaning: “We’re all Americans … it was like ‘Go America!’… We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see”. Immortalized in the 1970 documentary film, Woodstock, his guitar-driven version would become part of the sixties Zeitgeist. Pop critic Al Aronowitz of The New York Post wrote: “It was the most electrifying moment of Woodstock, and it was probably the single greatest moment of the sixties.” Images of the performance showing Hendrix wearing a blue-beaded white leather jacket with fringe, a red head-scarf, and blue jeans are widely regarded as iconic pictures that capture a defining moment of the era. He played “Hey Joe” during the encore, concluding the 3½-day festival. Upon leaving the stage, he collapsed from exhaustion. In 2011, the editors of Guitar World placed his rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Woodstock at number one in their list of his 100 greatest performances.

Although the details of Hendrix’s last day and death are widely disputed, he spent much of September 17, 1970, in London with Monika Dannemann, the only witness to his final hours. Dannemann said that she prepared a meal for them at her apartment in the Samarkand Hotel, 22 Lansdowne Crescent, Notting Hill, sometime around 11 p.m., when they shared a bottle of wine. She drove Hendrix to the residence of an acquaintance at approximately 1:45 a.m., where he remained for about an hour before she picked him up and drove them back to her flat at 3 a.m. Dannemann said they talked until around 7 a.m., when they went to sleep. She awoke around 11 a.m., and found Hendrix breathing, but unconscious and unresponsive. She called for an ambulance at 11:18 a.m., which arrived on the scene at 11:27 a.m. Paramedics then transported Hendrix to St Mary Abbot’s Hospital where Dr. John Bannister pronounced him dead at 12:45 p.m. on September 18, 1970.

To determine the cause of death, coroner Gavin Thurston ordered a post-mortem examination on Hendrix’s body, which was performed on September 21 by Professor Robert Donald Teare, a forensic pathologist. Thurston completed the inquest on September 28, and concluded that Hendrix aspirated his own vomit and died of asphyxia while intoxicated with barbiturates. Citing “insufficient evidence of the circumstances”, he declared an open verdict. Dannemann later revealed that Hendrix had taken nine of her prescribed Vesparax sleeping tablets, 18 times the recommended dosage.

After Hendrix’s body had been embalmed by Desmond Henley, it was flown to Seattle, Washington, on September 29, 1970. After a service at Dunlop Baptist Church on October 1, it was interred at Greenwood Cemetery in Renton, Washington, the location of his mother’s gravesite. Hendrix’s family and friends traveled in twenty-four limousines and more than two hundred people attended the funeral, including several notable musicians such as original Experience members Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, as well as Miles Davis, John Hammond, and Johnny Winter

Written by Dianne Washington