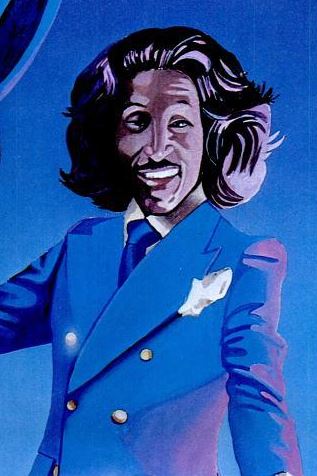

Frankie “Hollywood” Crocker (December 18, 1937 – October 21, 2000) was an American disc jockey who helped grow WBLS, the black music radio station in New York.

According to popeducation.org, Crocker began his career in Buffalo at the AM Soul powerhouse WUFO (also the home to future greats Gerry Bledsoe, Eddie O’Jay, Herb Hamlett, Gary Byrd and Chucky T) before moving to Manhattan, where he first worked for Soul station WWRL and later top-40 WMCA in 1969. He then worked for WBLS as program director, taking that station to the top of the ratings during the late 1970s and pioneering the radio format now known as urban contemporary. He sometimes called himself the Chief Rocker, and he was as well known for his boastful on-air patter as for his off-air flamboyance.

When Studio 54 was at the height of its popularity, Crocker once rode in through the front entrance on a white stallion.[4] In the studio, before he left for the day, Crocker would light a candle and invite female listeners to enjoy a candlelight bath with him. He signed off the air each night to the tune “Moody’s Mood For Love” by vocalese crooner King Pleasure. Crocker, a native of Buffalo, coined the phrase “urban contemporary” in the 1970s, a label for the eclectic mix of songs that he played.

He’d been the program director at WWRL and felt held back by what he considered to be the narrow perspective of the station. He quit and was twice re-hired by the station management; “He knew how to attract attention,” the chairman of Inner City Broadcasting, Hal Jackson was the owner of WBLS and once said, “We called him Hollywood.”

By 1979 he was shuttling between the west and east coast, with programming duties at KUTE in L.A. which featured R&B before a format change instituted there and on the east coast at WBLS which he called “Disco and More”, relying on his expertise at “finding the music”. Speaking to Radio Report magazine, an industry periodical, Crocker said, “There is nothing I won’t play if I hear it and like it and feel it will go for my market”.

WBLS-FM broke Blondie, Madonna, Shannon, D Train, all Arthur Baker records, The System, Colonel Abrams, Alicia Myers and supermodel Grace Jones. He made, “Love is the Message” by MFSB NYC’s unofficial anthem on the radio. WBLS airplay made “Ain’t No Stoppin Us Now” by McFadden and Whitehead a favorite cookout, church, wedding and graduation song. “The Magnificent Seven” by the Clash became a hot song in the Black Community. He gave America exposure to an obscure genre called “Reggae” and a little-known Jamaican rocker named Bob Marley. Fatback Band frontman Bill Curtis credited Crocker with breaking the group in New York.

Crocker was the master of ceremonies of shows at the Apollo Theater in Harlem and was one of the first VJs on VH-1, the cable music video channel, in addition to hosting the TV series Solid Gold and NBC’s Friday Night Videos. As an actor, Crocker appeared in five films, including Cleopatra Jones (1973), Five on the Black Hand Side (1973), and Darktown Strutters (Get Down and Boogie) (1975).

He is credited with introducing as many as 30 new artists to the mainstream, including Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa” to American audiences. While both Gary Byrd and Herb Hamlett were influenced by Crocker, it is only Hamlett who always attributes his success to his mentor in Buffalo, Frankie Crocker.

Frankie Crocker was inducted into the Buffalo Broadcasting Hall of Fame in 2000 and the New York State Broadcasters Association Hall of Fame in 2005.

Crocker was indicted as a result of a 1976 payola investigation; the charges were later dismissed.[13] After he was charged, the radio station dropped him, and Crocker moved to L.A. and returned to school.

After the payola charges were dismissed, he returned to New York radio in 1979 as DJ and Program Director on WBLS-FM, at the end of the disco era. Crocker’s career in radio ended by 1985. He moved to MTV as a VJ on the VH-1 cable channel.

In October 2000, Crocker went into a Miami area hospital for several weeks. He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and kept the illness a secret from his friends and even from his mother. He died on October 21, 2000. His friend and former boss Bob Law, a onetime program director of WWRL, said of Crocker, “He encompassed all of the urban sophistication. He appreciated the culture, the whole urban experience, and he wove it together. That’s missing now, even in black radio”.

Written by Dianne Washington