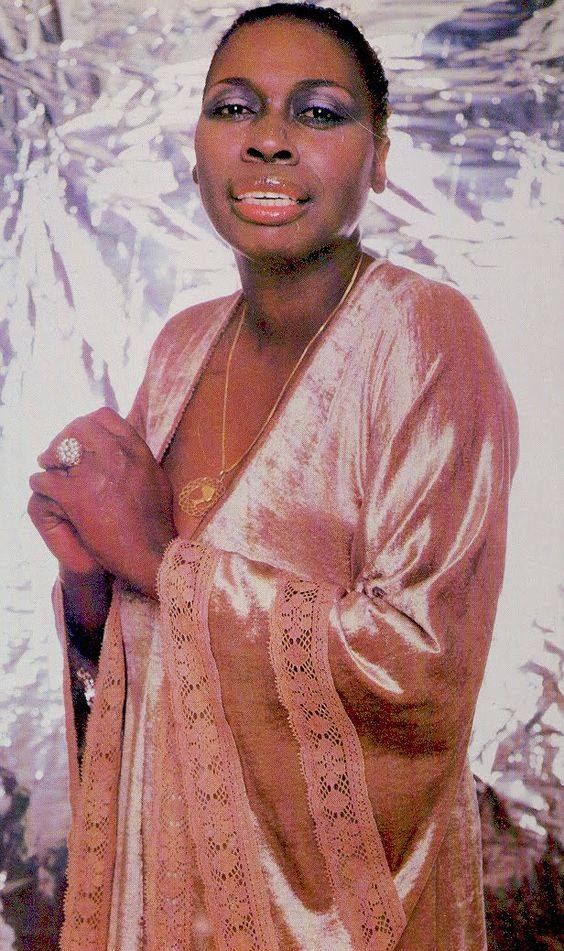

Esther Phillips (born Esther Mae Jones; December 23, 1935 – August 7, 1984) was an American singer, best known for her R&B vocals. She was a versatile singer and also performed pop, country, jazz, blues and soul music.

Born Esther Mae Jones in Galveston, Texas, she began singing in church as a young child. When her parents divorced, she divided her time between her father in Houston and her mother in the Watts area of Los Angeles. She was brought up singing in church and was reluctant to enter a talent contest at a local blues club, but her sister insisted. A mature singer at the age of 14, she won the amateur talent contest in 1949 at the Barrelhouse Club, owned by Johnny Otis. Otis was so impressed that he recorded her for Modern Records and added her to his traveling revue, the California Rhythm and Blues Caravan, billed as Little Esther. She later took the surname Phillips, reportedly inspired by a sign at a gas station.

Billed as Little Esther, she scored her first success when she was teamed with the vocal quartet the Robins (who later evolved into the Coasters) on the hit single “Double Crossin’ Blues.” It topped the R&B charts in early 1950 and paved the way for “Mistrustin’ Blues,” “Misery,” “Cupid Boogie,” and “Deceivin’ Blues.” In 1951, Little Esther and Otis had a falling out, reportedly over money, which led to her departure from his show.

Her first hit record was “Double Crossing Blues”, with the Johnny Otis Quintette and the Robins (a vocal group), released in 1950 by Savoy Records, which reached number 1 on the Billboard R&B chart. She made several hit records for Savoy with the Johnny Otis Orchestra, including “Mistrusting Blues” (a duet with Mel Walker) and “Cupid’s Boogie”, both of which also went to number 1 that year. Four more of her records made the Top 10 in the same year: “Misery” (number 9), “Deceivin’ Blues” (number 4), “Wedding Boogie” (number 6), and “Far Away Blues (Xmas Blues)” (number 6). Few female artists performing in any genre had such success in their debut year.

Phillips left Otis and the Savoy label at the end of 1950 and signed with Federal Records. But just as quickly as the hits had started, they stopped. She recorded more than thirty sides for Federal, but only one, “Ring-a-Ding-Doo”, made the charts, reaching number 8 in 1952. Not working with Otis was part of her problem; the other part was her deepening dependence on heroin, to which she was addicted by the middle of the decade. Being in the same room when Johnny Ace shot himself (accidentally) on Christmas Day, 1954, while in-between shows in Houston, presumably did not help matters.

In 1954, she returned to Houston to live with her father and recuperate. Short on money, she worked in small nightclubs around the South, punctuated by periodic hospital stays in Lexington, Kentucky, to treat her addiction. In 1962, Kenny Rogers discovered her singing at a Houston club and helped her get a contract with Lenox Records, owned by his brother Lelan.

In 1954, she returned to Houston to live with her father, having experimented with hard drugs, developing an addiction to heroin. Short on money, Little Esther worked in small nightclubs around the South, punctuated by periodic hospital stays in Lexington, Kentucky, stemming from her addiction.

In 1962, Kenny Rogers got her signed to his brother’s Lenox label, rediscovering her while singing at a Houston club. She re-christened herself Esther Phillips, choosing her last name from a nearby Phillips gas station. Phillips recorded a country-soul rendition of the soon-to-be standard “Release Me,” which was a smash, topping the R&B charts and hitting the Top Ten on both the pop and country charts. Back in the public eye, Phillips recorded a country-soul album of the same name, but Lenox went bankrupt in 1963. Thanks to her recent success, Phillips was able to catch on with R&B giant Atlantic.

Her remake of the Beatles song “And I Love Him” (naturally, with the gender changed) nearly made the R&B Top Ten in 1965 and the Beatles flew her to the U.K. for her first overseas performances. Encouraged, Atlantic pushed her into even jazzier territory for her next album, but none of the resulting singles really caught on and the label dropped her in late 1967.

With her addiction worsening, Phillips checked into a rehab facility; while undergoing treatment, she cut some sides for Roulette in 1969 and upon her release, she moved to Los Angeles and re-signed with Atlantic.

In 1971, she signed with producer Creed Taylor’s Kudu label, a subsidiary of his hugely successful jazz-fusion imprint CTI. Her label debut, “From a Whisper to a Scream,” was released in 1972 to strong sales and highly positive reviews, particularly for her performance of Gil Scott-Heron’s wrenching heroin-addiction tale, “Home Is Where the Hatred Is.” Phillips recorded several more albums for Kudu over the next few years and enjoyed some of the most prolonged popularity of her career, performing in high-profile venues and numerous international jazz festivals.

In 1975, she scored her biggest hit single since “Release Me” with “What a Difference a Day Makes” (Top Ten R&B, Top 20 pop), and the accompanying album of the same name became her biggest seller yet. In 1977, Phillips left Kudu for Mercury, but none matched the commercial success of her Kudu output and after 1981’s “A Good Black Is Hard to Crack,” she found herself without a record deal.

Esther Phillips was perhaps too versatile for her own good; her voice had an idiosyncratic, nasal quality that often earned comparisons to Nina Simone, although she herself counted Dinah Washington as a chief inspiration.

Phillips died at UCLA Medical Center in Carson, California, in 1984, at the age of 48, from liver and kidney failure due to long-term drug abuse. Her funeral services were conducted by Johnny Otis. Originally buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave at Lincoln Memorial Park in Compton, she was reinterred in 1985 in the Morning Light section at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Hollywood Hills, in Los Angeles. A bronze marker recognizes her career achievements and quotes a Bible passage: “In My Father’s House Are Many Mansions” (John 14:2).

Written by Dianne Washington