Robert Nesta Marley, (February 6, 1945 – May 11, 1981) was a Jamaican singer-songwriter who became an international musical and cultural icon, blending mostly reggae, ska and rocksteady in his compositions. Starting out in 1963 with the group the Wailers, he forged a distinctive songwriting and vocal style that would later resonate with audiences worldwide. The Wailers would go on to release some of the earliest reggae records with producer Lee “Scratch” Perry.

After the Wailers disbanded in 1974, Marley pursued a solo career upon his relocation to England that culminated in the release of the album Exodus in 1977, which established his worldwide reputation and elevated his status as one of the world’s best-selling artists of all time, with sales of more than 75 million records. Exodus stayed on the British album charts for 56 consecutive weeks. It included four UK hit singles: “Exodus”, “Waiting in Vain”, “Jamming”, and “One Love”. In 1978, he released the album Kaya, which included the hit singles “Is This Love” and “Satisfy My Soul”. The greatest hits album, Legend, was released in 1984, three years after Marley died. It subsequently became the best-selling reggae album of all time.

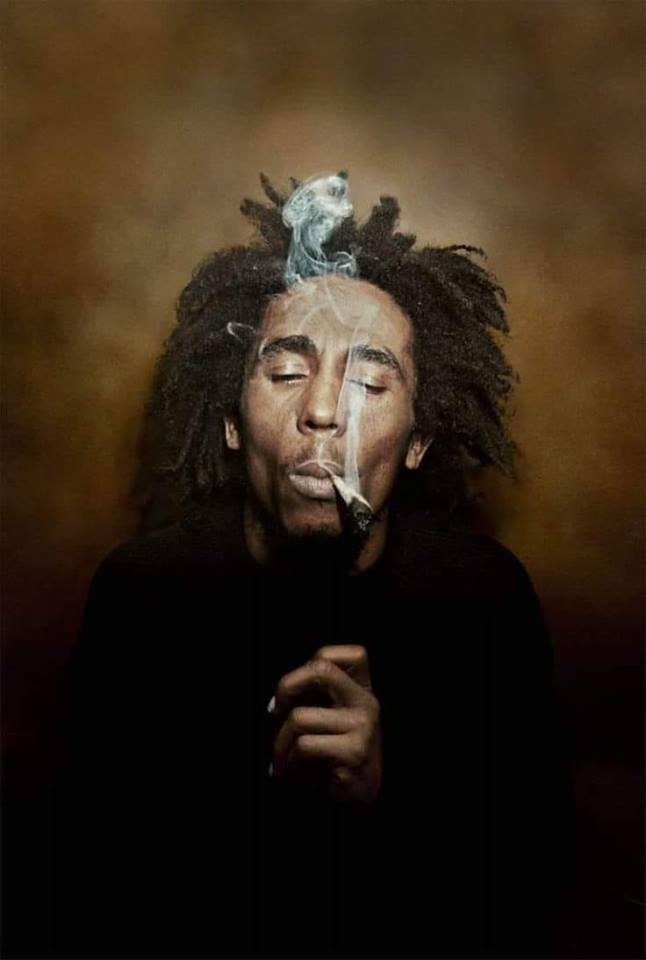

Diagnosed with acral lentiginous melanoma in 1977, Marley died on 11 May 1981 in Miami at age 36. He was a committed Rastafari who infused his music with a sense of spirituality. He is credited with popularising reggae music around the world and served as a symbol of Jamaican culture and identity. Marley has also evolved into a global symbol and inspired numerous items of merchandise.

Bob Marley was born Robert Nesta Marley in rural Rhoden Hall in the Parish of St. Ann, Jamaica. His mother was a Jamaican teenager and his father a middle-aged captain in the West Indian regiment of the British Army. Marley’s parents separated when he was six and soon thereafter Robert moved with his mother to Kingston, joining the wave of rural immigrants that flooded the capital during the 1950s and 1960s. They settled in Trench Town, a west Kingston slum named for the sewer that ran through it. There, Marley shared quarters with a boy his age named “Bunny” Neville O’Riley Livingston. The two made music together, making a guitar from bamboo, sardine cans, and electrical wire and learning harmonies from local singer Joe Higgs.

Like a number of their generation, Marley and Bunny listened to radio from New Orleans; and they embraced the sounds of rhythm and blues, combining them with pieces of their musical style, producing a new music called ska. Although encouraged by his mother to learn a craft, Marley soon abandoned an apprenticeship as a welder to devote himself to music. In the 1960s, Peter McIntosh (later Peter Tosh) joined Bunny and Marley’s musical sessions, bringing a real guitar and the three formed the Wailing Wailers. During this time, Marley recorded a few songs with producer Leslie Kong, introduced to him through local ska celebrity Jimmy Cliff.

Marley’s earliest recordings received little radio play but strengthened his desire to sing. Joined by Junior Braithwaite and two backup singers, the Wailing Wailers recorded on the Coxsone label, supervised by Clement Dodd. The group became Kingston celebrities in the summer of 1963 with Simmer Down, a song that both indicted and romanticized the lives of Trench Town toughs, known as “rude boys.” The Wailing Wailers recorded more than 30 singles in the mid-1960s, reflecting and sometimes leading the evolution of reggae, from mento to ska to rock steady. In 1963 his mother moved to Delaware, Marley followed with a lengthy visit in 1966, working jobs for Chrysler and Dupont. Yet his heart lay back home, where his new wife, Jamaican Rita Anderson, and his old passion the music of the island remained.

When he returned to home in 1967 he converted from Christianity to Rastafarianism and began the mature stage of his musical career. Marley reunited with Bunny and Peter Tosh, and together they called themselves The Wailers and began their own record label, Wail ‘N’ Soul. They abandoned the rude-boy philosophy for the spirituality of Rastafarian beliefs slowing their music under the new “rock steady” influence. Although the Wailers began to fit together as a group, they did not find success beyond Jamaica. In 1970 bassist Aston “Family Man” Barnett and his drummer joined the Wailers. With this addition the group attracted the attention of Island Records, a company that had started in Jamaica but moved to London.

In 1971 they recorded Catch a Fire, the first Jamaican reggae album to enjoy the benefits of a large budget and widespread commercial promotion. Catch a Fire sold modestly, better in Europe than America, but well enough to sustain the company’s interest in the group. During the early 1970s the band recorded an album each year and toured extensively, slowly breaking into the European and American markets. They played shows with Americans Bruce Springsteen and Sly & the Family Stone, and in 1974 Briton’s Eric Clapton scored a hit with I Shot the Sheriff, a Marley composition.

The next year, The Wailers made their first major splash in the United States with No Woman No Cry and an album of live material. At this point, however, Peter Tosh and Bunny left the band, they then took the name Bob Marley & the Wailers. Although Marley had blended politics and music since the early days of “Simmer Down,” as his success grew he became more political. His 1976 song War transcribed a speech of Haile Selassie I, the Ethiopian king upon whom the Rastafarian sect was based. Along with Rastafarian spirituality and mysticism, his lyrics probed the turmoil in Jamaica. Prior to the 1976 elections, partisanship inspired gang war in Trench Town and divided the people against themselves.

By siding with Prime Minister Michael Manley and by singing songs of a political tone Marley angered some Jamaicans. After surviving an assassination attempt in December he fled to London until the following year. When Marley returned to Jamaica in 1978, he performed in the One Love Peace Concert, seeking to improve existing political conflicts. During this show Marley orchestrated a handshake between political opponents Manley and Edward Seaga, a highly symbolic moment. Marley’s activism extended beyond Jamaica, and people from developing nations around the world found hope in his music.

The group’s concerts in the late 1970s attracted enormous crowds in West Africa, Latin America, in Europe and the United States. In 1980 Bob Marley & the Wailers had the honor of performing at the independence ceremony when Rhodesia became Zimbabwe. His music became closely associated with the movement toward Black political independence that was then prominent in several African and South American countries. The first global pop star to emerge from a developing nation.

Marley’s last concert occurred at the Stanley Theater (now called The Benedum Center For The Performing Arts) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on September 23, 1980. Just two days earlier he had collapsed during a jogging tour in Central Park and was brought to hospital where he learned that the cancer had spread to his brain.

The only known photographs from the show were featured in Kevin Macdonald’s documentary film Marley.

Shortly afterwards, Marley’s health deteriorated as the cancer had spread throughout his body. The rest of the tour was cancelled and Marley sought treatment at the Bavarian clinic of Josef Issels, where he received an alternative cancer treatment called Issels treatment partly based on avoidance of certain foods, drinks, and other substances. After fighting the cancer without success for eight months Marley boarded a plane for his home in Jamaica.

While Marley was flying home from Germany to Jamaica, his vital functions worsened. After landing in Miami, Florida, he was taken to the hospital for immediate medical attention. Marley died on May 11, 1981 at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Miami (now University of Miami Hospital), aged 36. The spread of melanoma to his lungs and brain caused his death. His final words to his son Ziggy were “Money can’t buy life.”

Marley received a state funeral in Jamaica on May 21, 1981, which combined elements of Ethiopian Orthodoxy and Rastafari tradition. He was buried in a chapel near his birthplace with his red Gibson Les Paul (some accounts say it was a Fender Stratocaster).